PAINTINGS / PINTURAS

[Artist's statement about paintings]

Featured Paintings

Leopardo de Nieve (1969)

Retrato Doble (1970)

Sueño (1971)

Janis Joe (Janis Joplin and Joe Cocker) (1971)

Karl Marx (1972)

Violeta Parra (1973)

Frente Cultural (1973)

Martillo y Repollo (1973)

Angel de la Menstruación (1973)

"I began painting early on. I did mostly abstract art, solar signs, and marks, until one day, in 1969, I saw in my mind's eye a way to continue the tradition of the colonial 'saints,' subverted by an indigenous brush."

—Cecilia Vicuña

Excerpt from "Cecilia Vicuña's Calcomanías," by Dawn Adés:

“'I first create a plain, flat background, with a single, very diluted oil color that creates that liquid feeling. (I usually use burnt sienna, but have used other colors too), I let it dry somewhat, and then I draw with a very fine brush ("pincel de un pelo" said Nemesio Antúnez observing my technique), the outline of the work, with a clear oil color, with plenty of white, so that it will stand out against the background. I then "fill" the outline with color, transferring the image from my mind to the canvas. It is like drawing with oil on a receptive field. There is no room for mistake, b/c everything shows, and mistakes become part of the piece.' (Vicuña, Letter, 14 May 2013).

The term 'Calcomanía' acknowledges one of the surrealists’ favourite techniques, decalcomania, a kind of marbling where the automatic configurations of the wet ink or gouache are lightly interpreted. But the Calcomanías are not 'automatic' in the sense that decalcomanias were, that is, producing a wholly unguided visual field. Cecilia was painting an image that had sprung in her mind, unbidden, and that she then transferred in paint. But they belong within the same spectrum in its broadest sense, which was always surrealism’s terrain. As she wrote in Sabor a mí in 1973, 'Paintings coming out of darkness go back to darkness, automatic images issue from "regiones esquivas," elusive regions, and right after exposure, like dreams, they return to their burrows in inaccessible places' (Sabor a mí 75).

Her adoption of an apparently naïve manner is entirely distinctive; it was not a question of following any sets of rules or mimicking other surrealist painters, certainly not of proclaiming herself surrealist. Well versed in the history of European art, her paintings, which clearly rejected this, at first bewildered her cultivated family, her father lamenting 'What was the point of all your education? All the Renaissance books I gave you if you are going to paint like this?' In common with many Latin Americans, Cecilia’s family did not value indigenous or popular art, dismissing it as 'folkloric' and the Western taste for it as romantic. Like the surrealists, Cecilia makes no distinction between high, or elite, and popular art. Although she also scavenged images from further afield, the manner in which she 'transfers' those she 'saw' is rooted in the strange hybrid art of Latin America, the ways indigenous Indian painters translate into their own idioms European iconography, and whose flatness and surface details were often misunderstood by the Europeans as purely 'decorative,' although the art was invested with meanings within the indigenous cultures. Cecilia described the Calcomanías as continuations 'of how the Europeans had forced the Indians to paint these colonial flat images in a flat background, but the Indians subverted them to create their own Pachamamas, their own, you know, angels with guns, and things like that, so I would paint my own Chilean goddesses, that way, and again you see it’s a meeting point, a meeting point of the natives and civility, with the European imposition transformed' (Interview with Valerie Fraser, Santiago, January 2011, unpublished). So the complex to-and-fro between European and native traditions, iconographies, and practices contributed to her wholly original paintings."

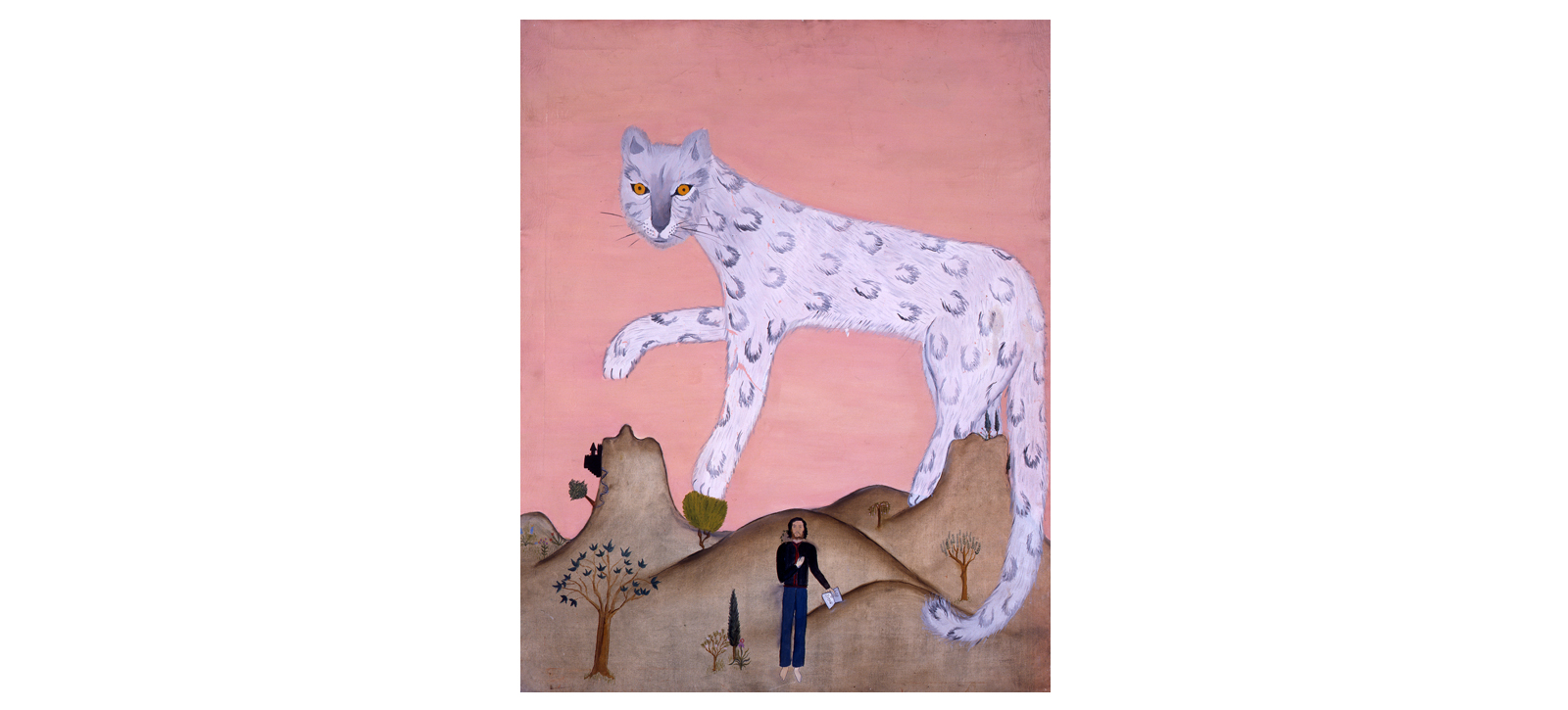

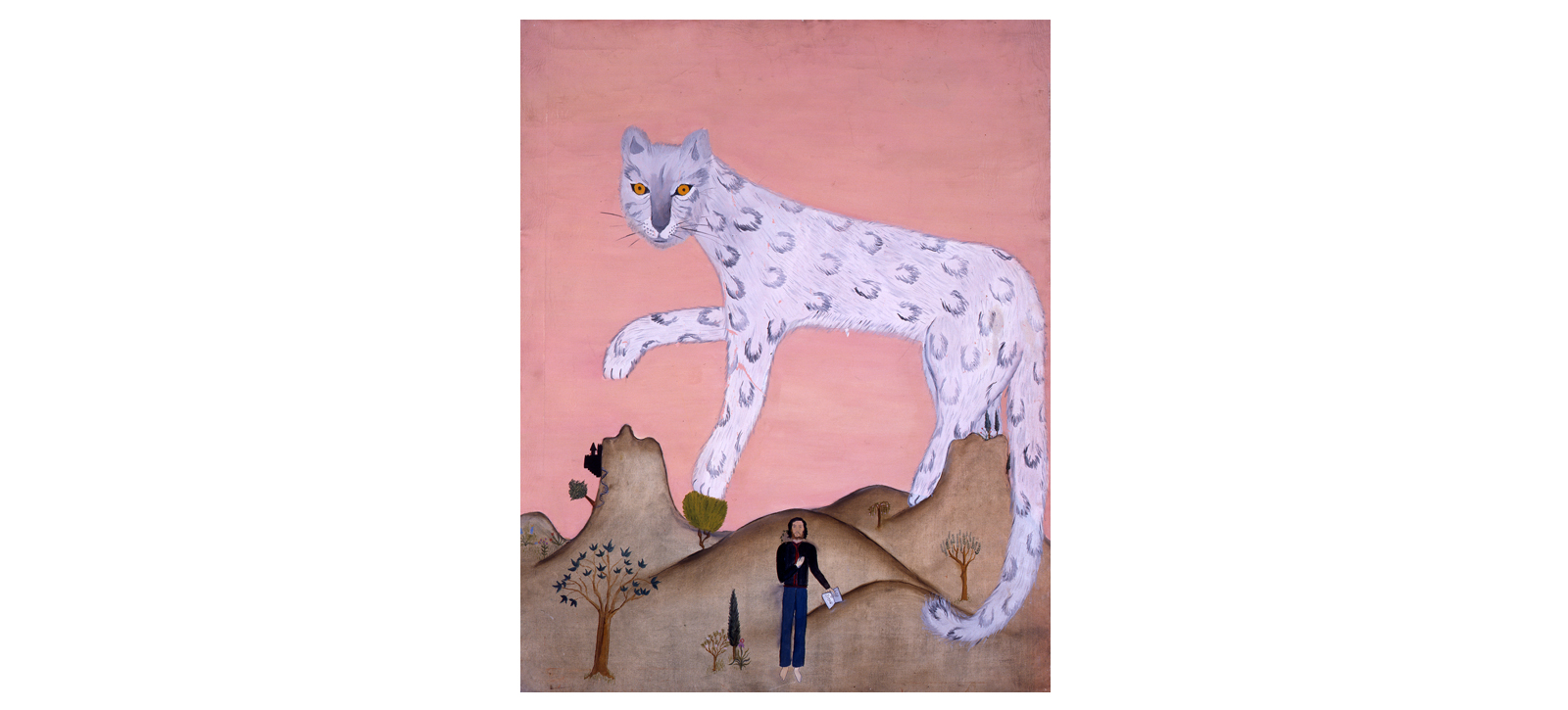

Leopardo de Nieve (1969)

Oil on canvas

70cm x 90cm

Collection of the artist

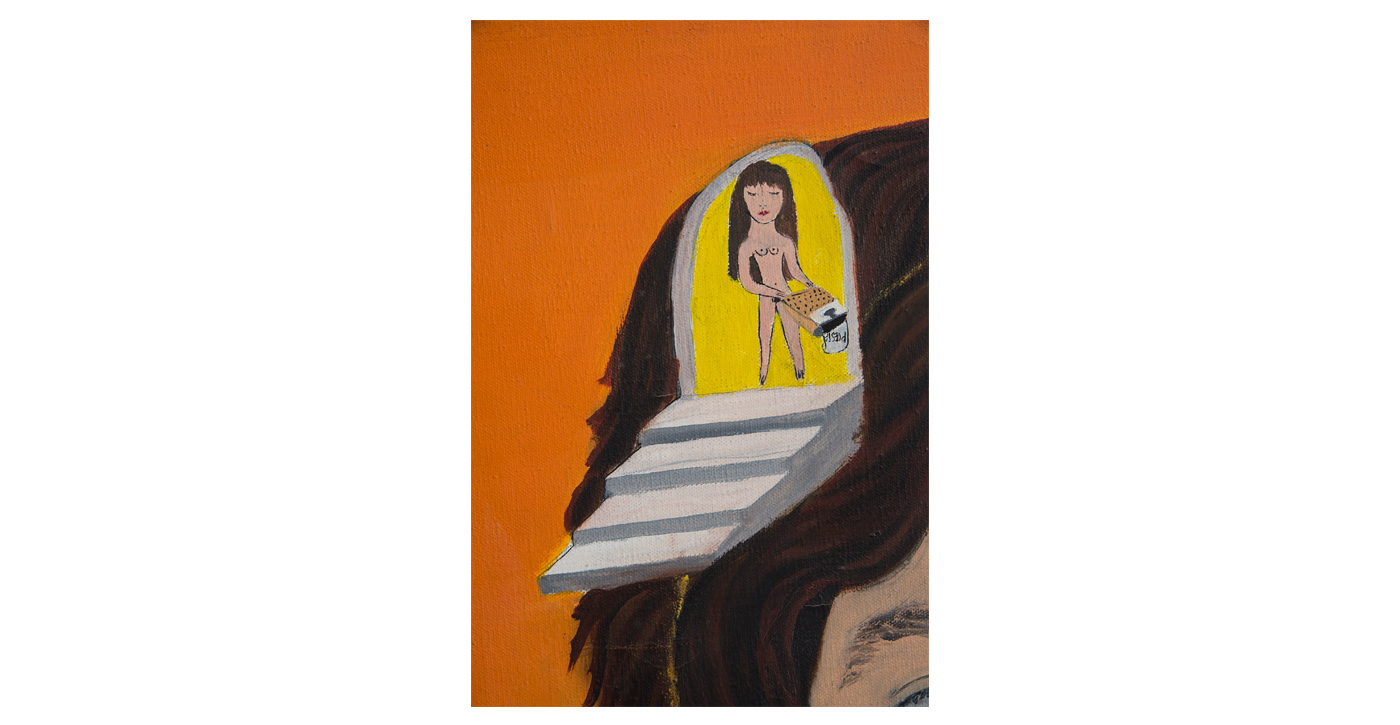

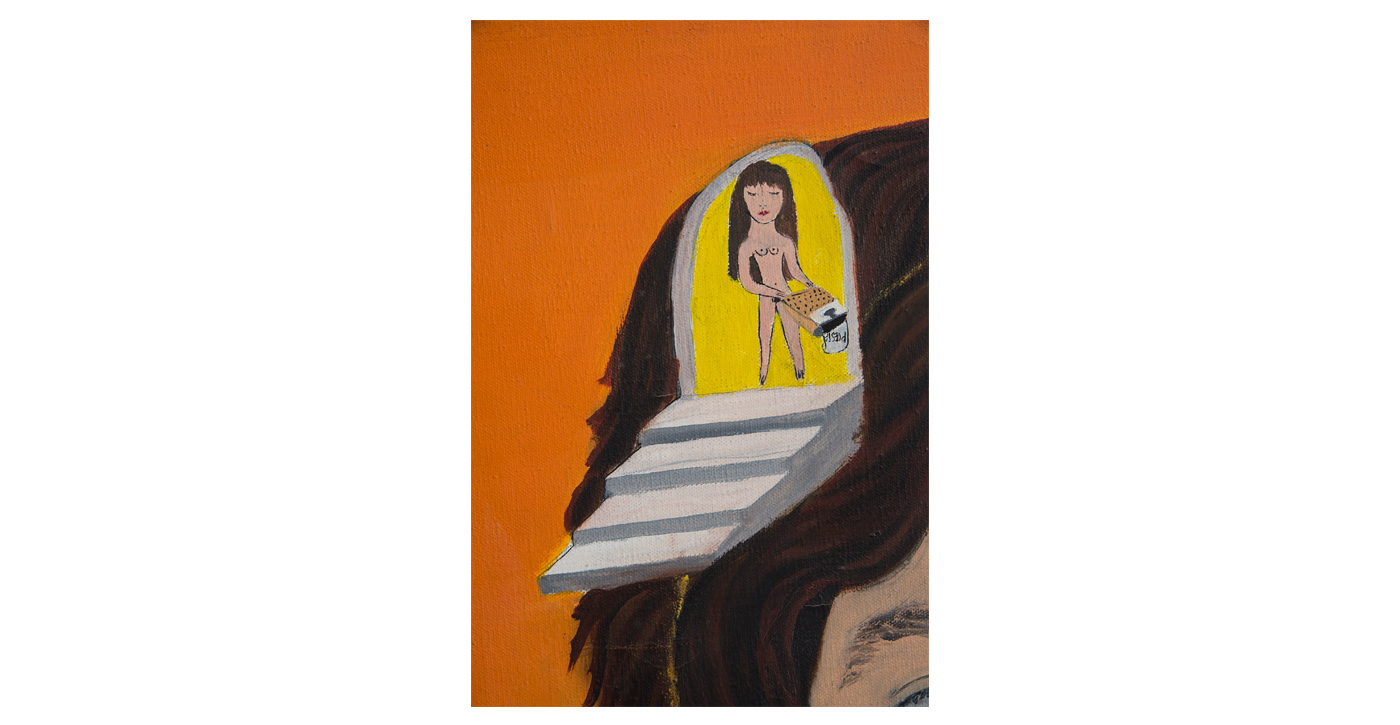

Retrato Doble (1970)

Oil on canvas

82 x 1.80cm

Collection of the National Museum of Fine Arts (MNBA), Santiago, Chile

detail from Retrato Doble (1970)

Sueño: the Indians kill the pope (1971)

Oil on canvas

59cm x 59cm

Collection of the artist

Santiago de Chile, March 1971

See also the book Sabor a mí

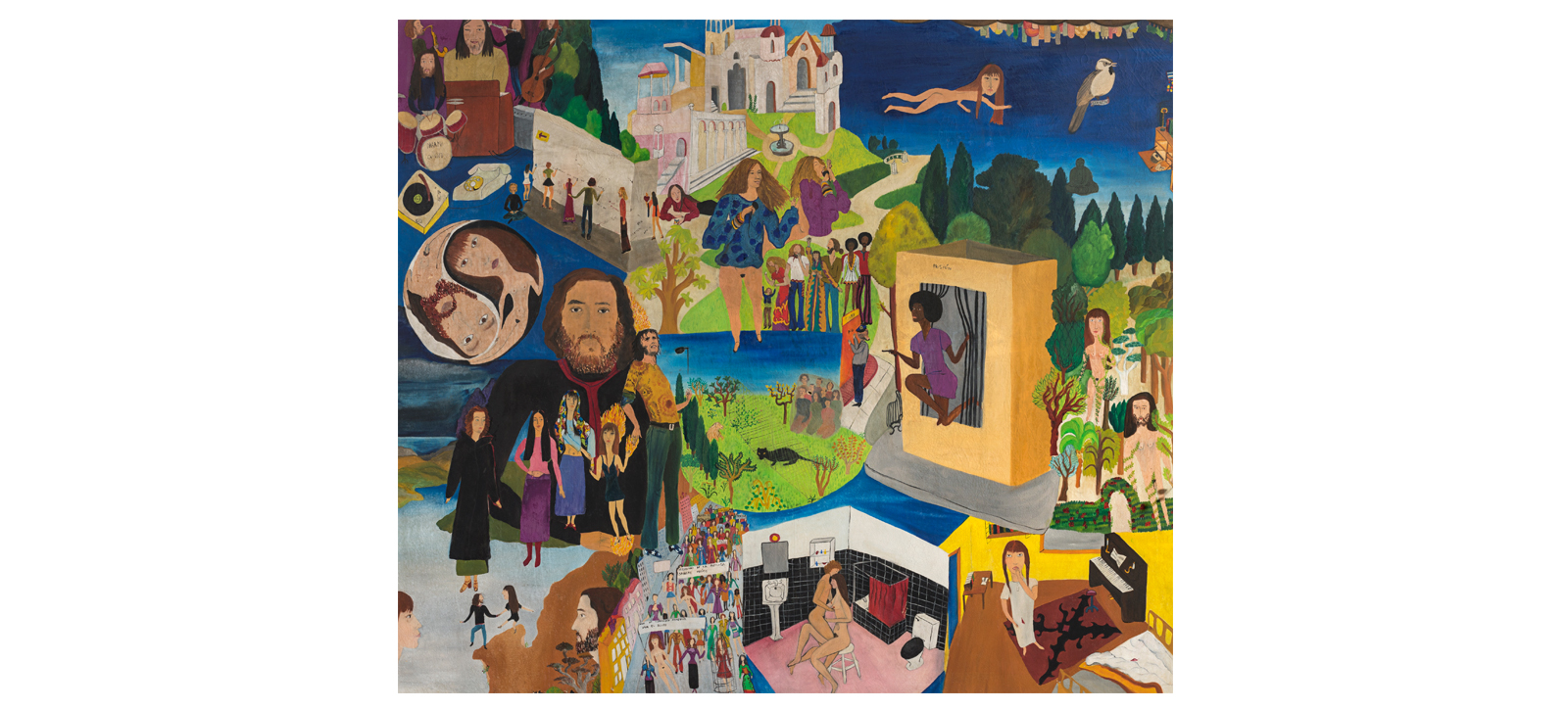

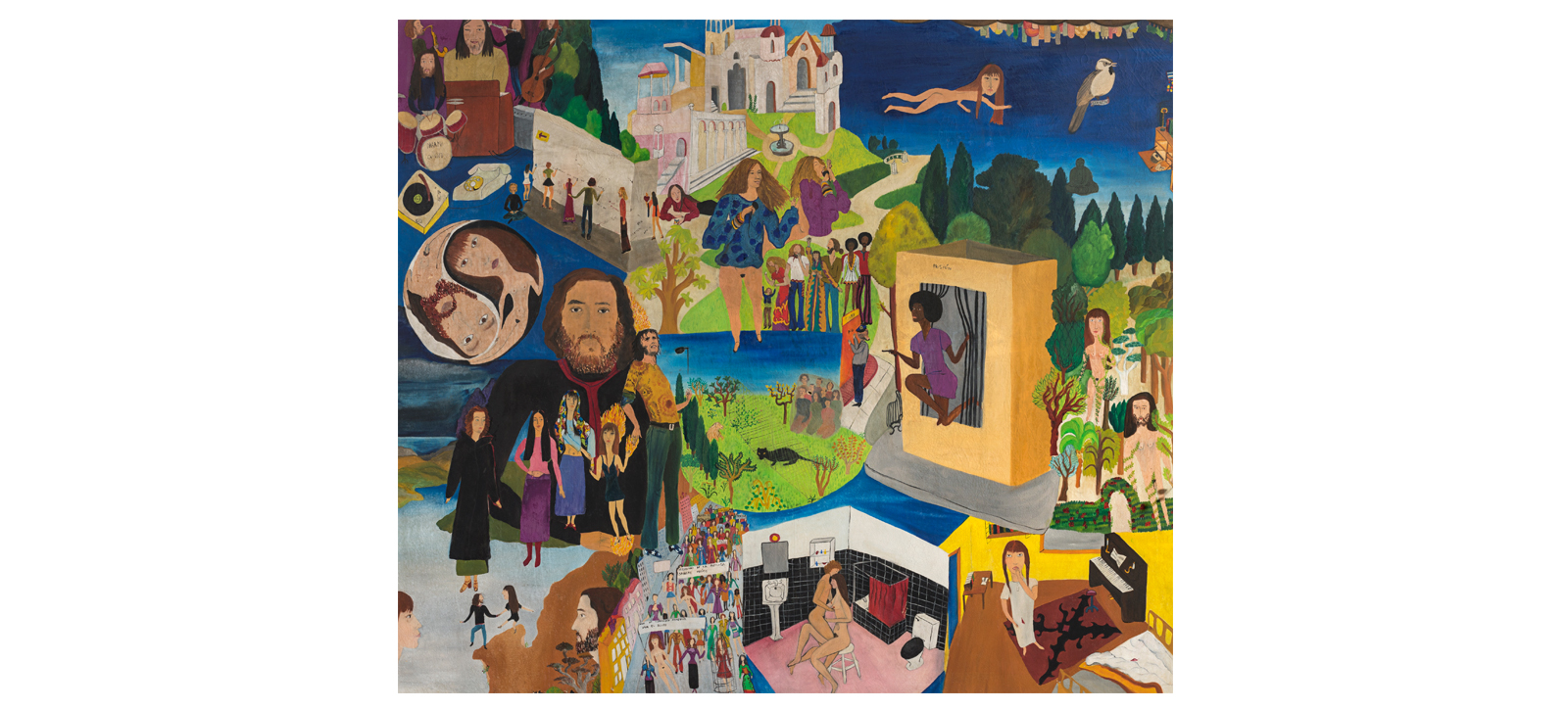

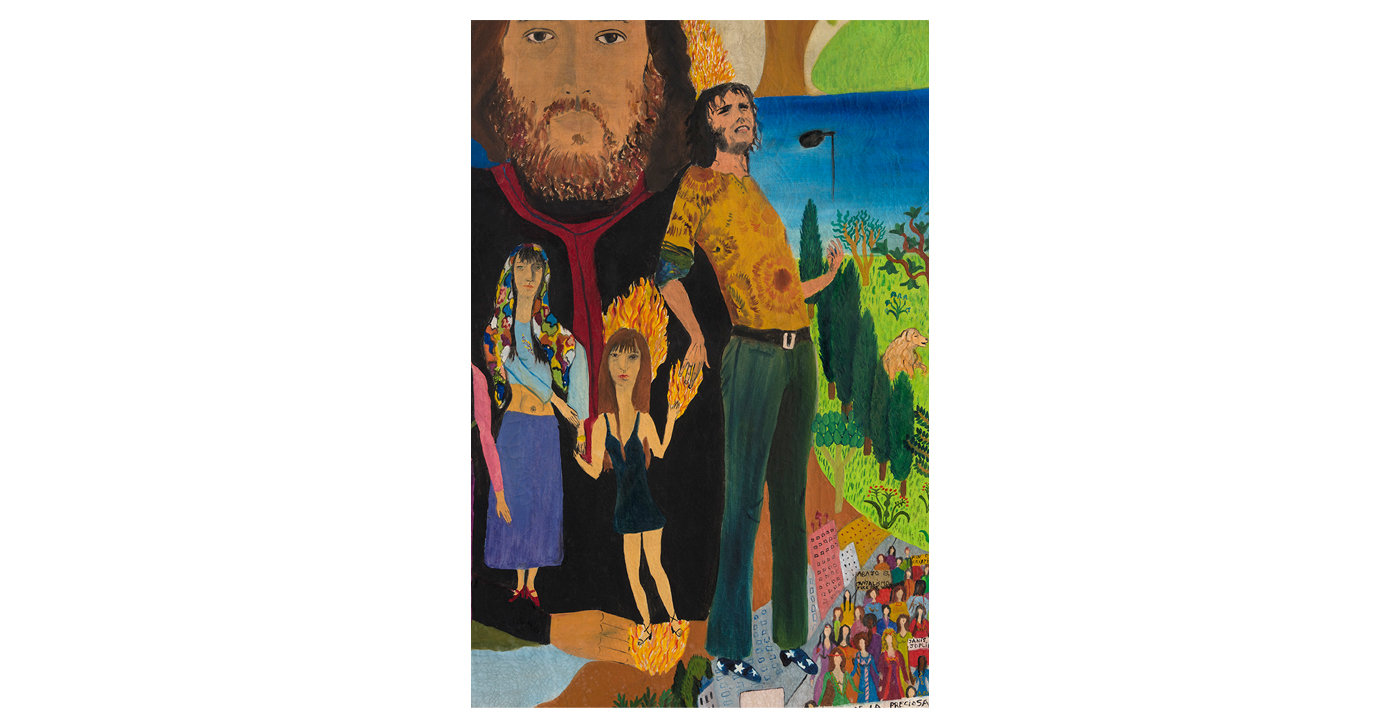

Janis Joe (Janis Joplin and Joe Cocker) (1971)

Oil on canvas

Approx. 200cm x 220cm

Private collection, Santiago, Chile

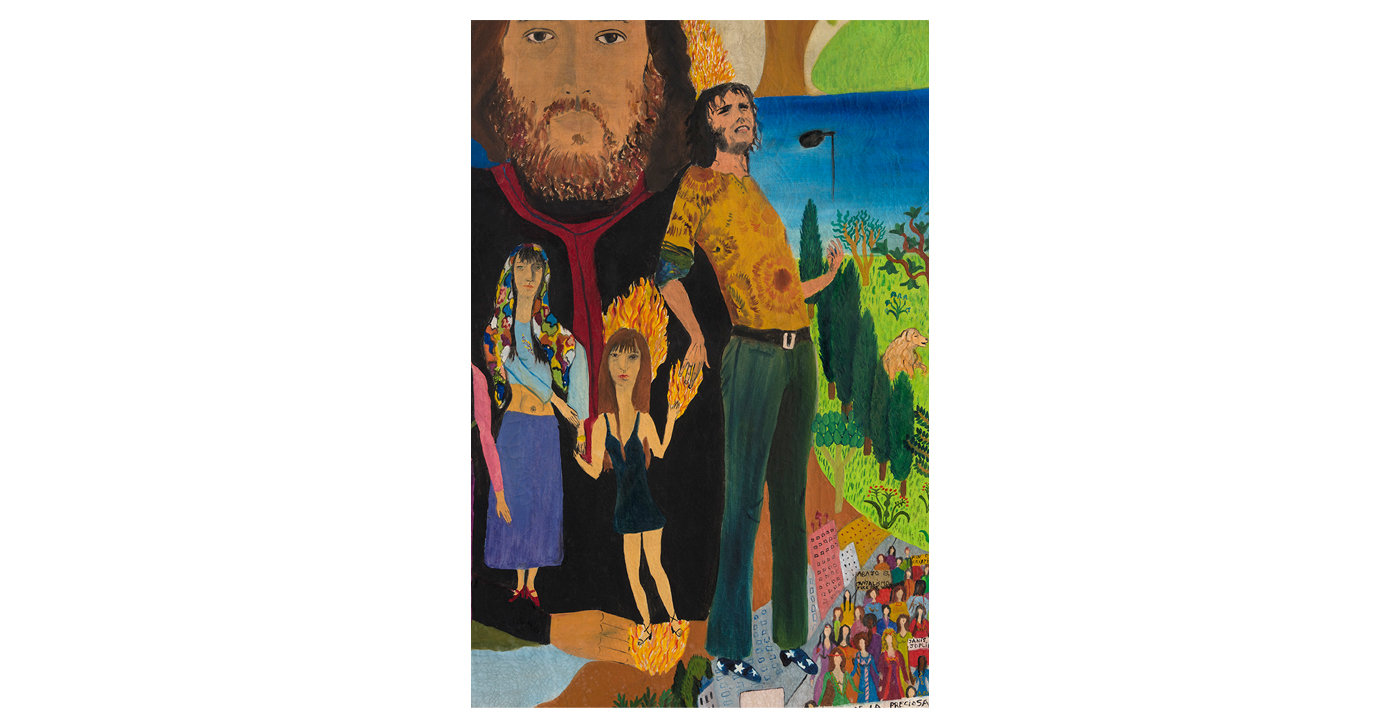

detail from Janis Joe (Janis Joplin and Joe Cocker) (1971)

detail from Janis Joe (Janis Joplin and Joe Cocker) (1971)

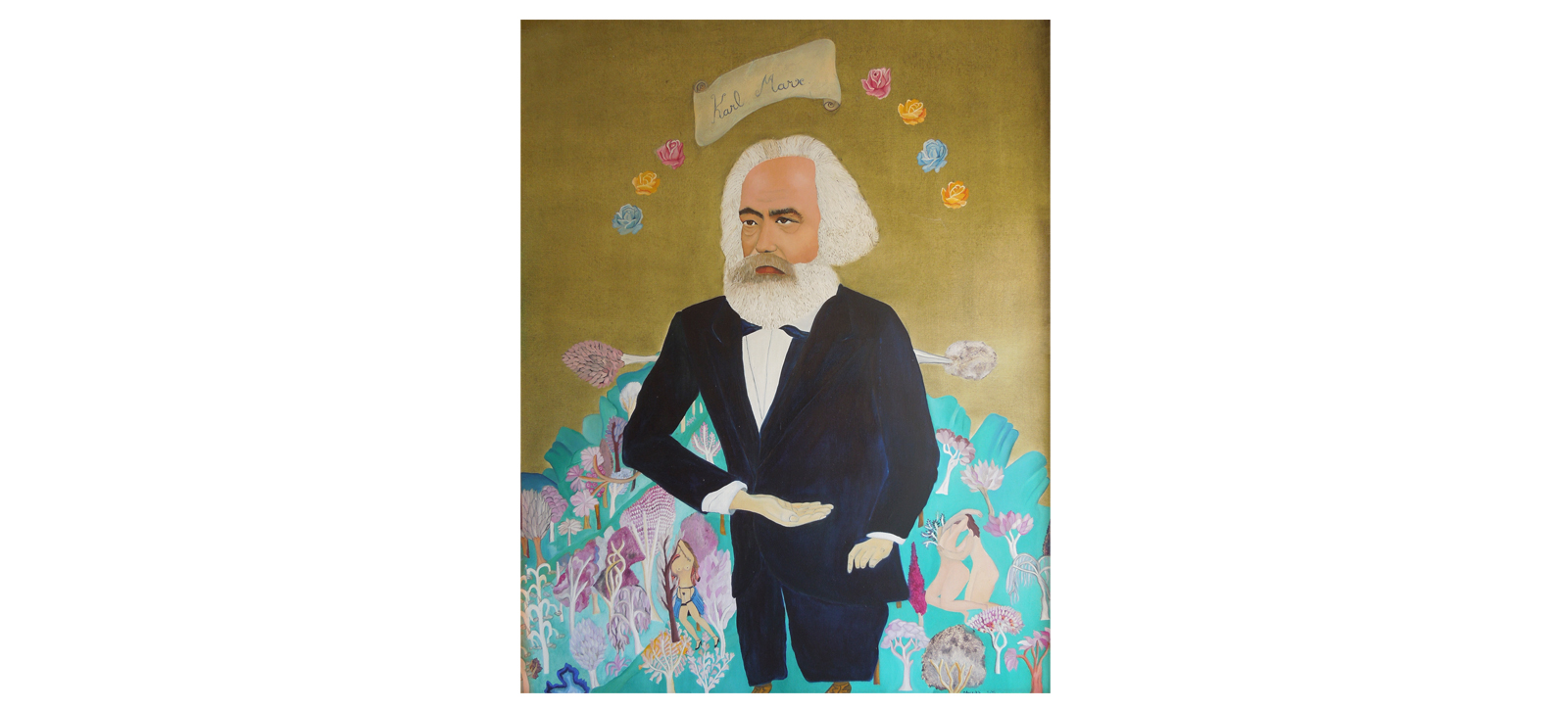

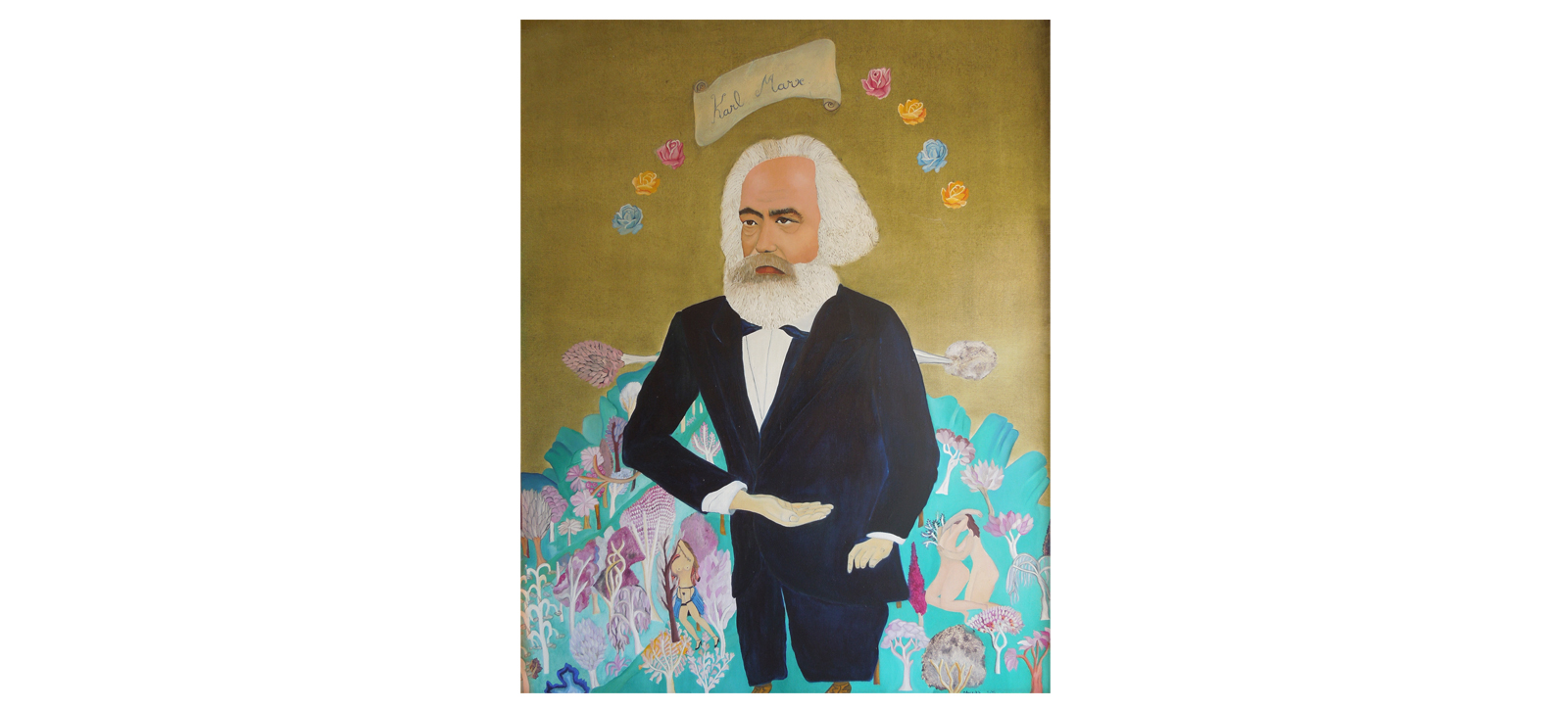

Karl Marx (1972)

Oil on canvas

Approx. 72cm x 90cm

Private collection, Santiago, Chile.

Violeta Parra o Violenta Vid (1973)

Oil on canvas

48cm x 58cm

Collection of the artist

"I decided to paint a portrait of Violeta Parra for the series of Heroes of the Revolution, because not all the heroes have to be leaders, thinkers or guerrillas, we also need heroes of being, painting and invention."

See also the book Sabor a Mi

See also Heroes of the Revolution

Frente Cultural (1973)

Oil on canvas

79cm x 63cm

Collection of the artist

The Cultural Front, painted in London, before the military coup of September 11th, 1973, it represents Chilean culture as "a circular animal, or an egg hatching the revolution" where "all media conform a colective universe, neither vertical nor horizontal, but circular."

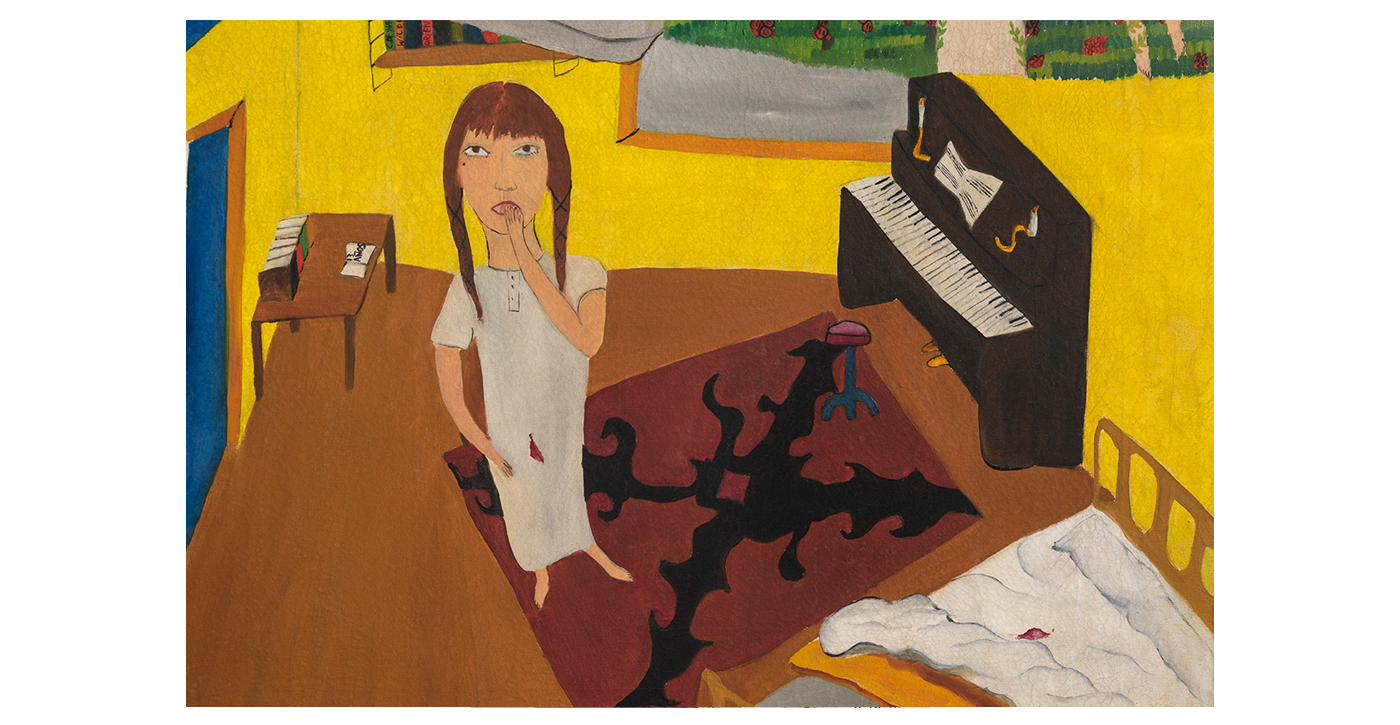

Martillo y Repollo (1973)

Oil on canvas

71.1cm x 91cm

Collection of the artist

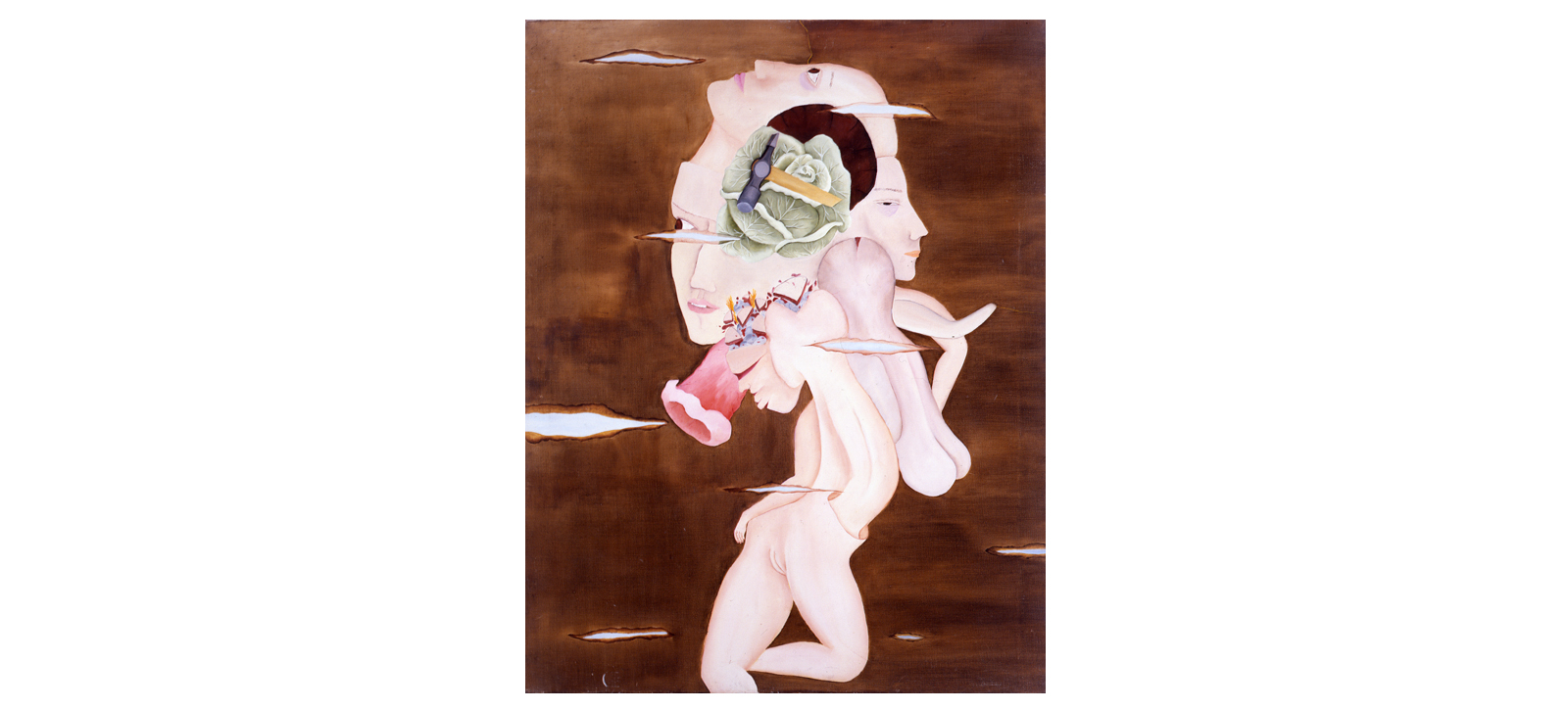

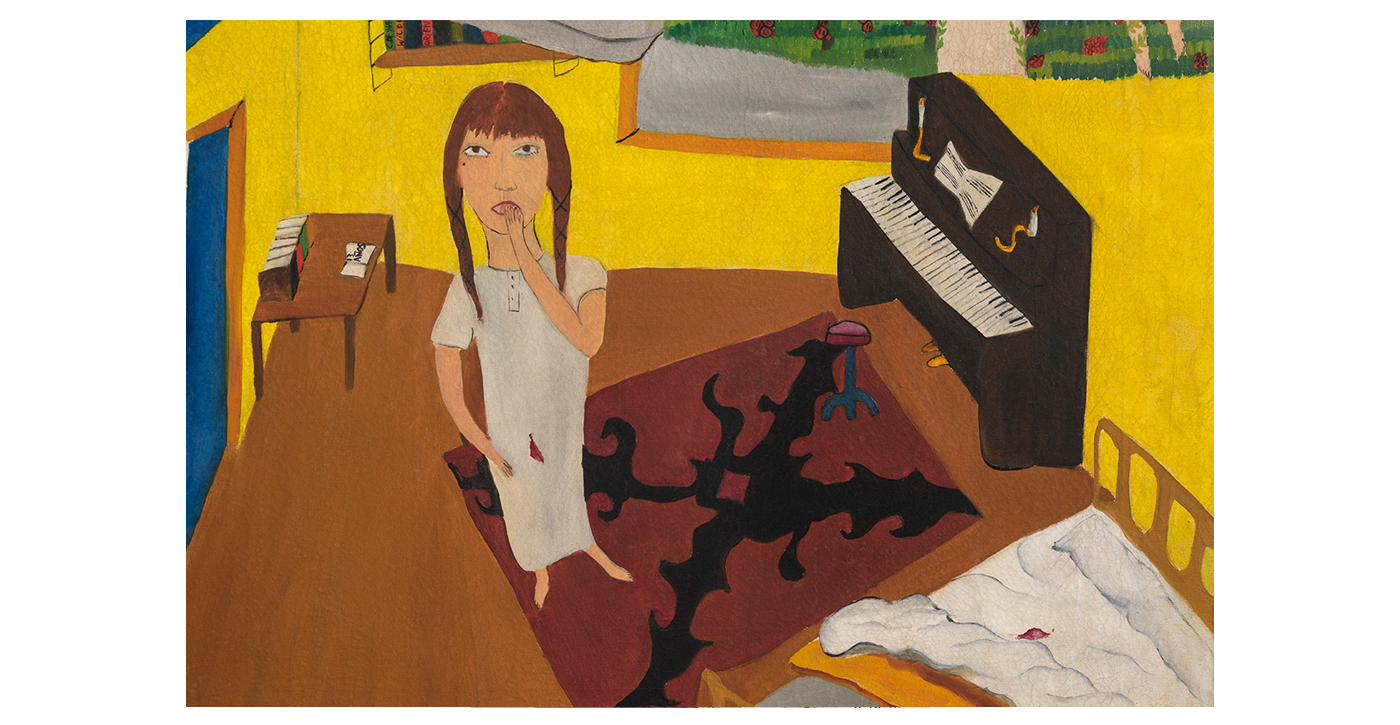

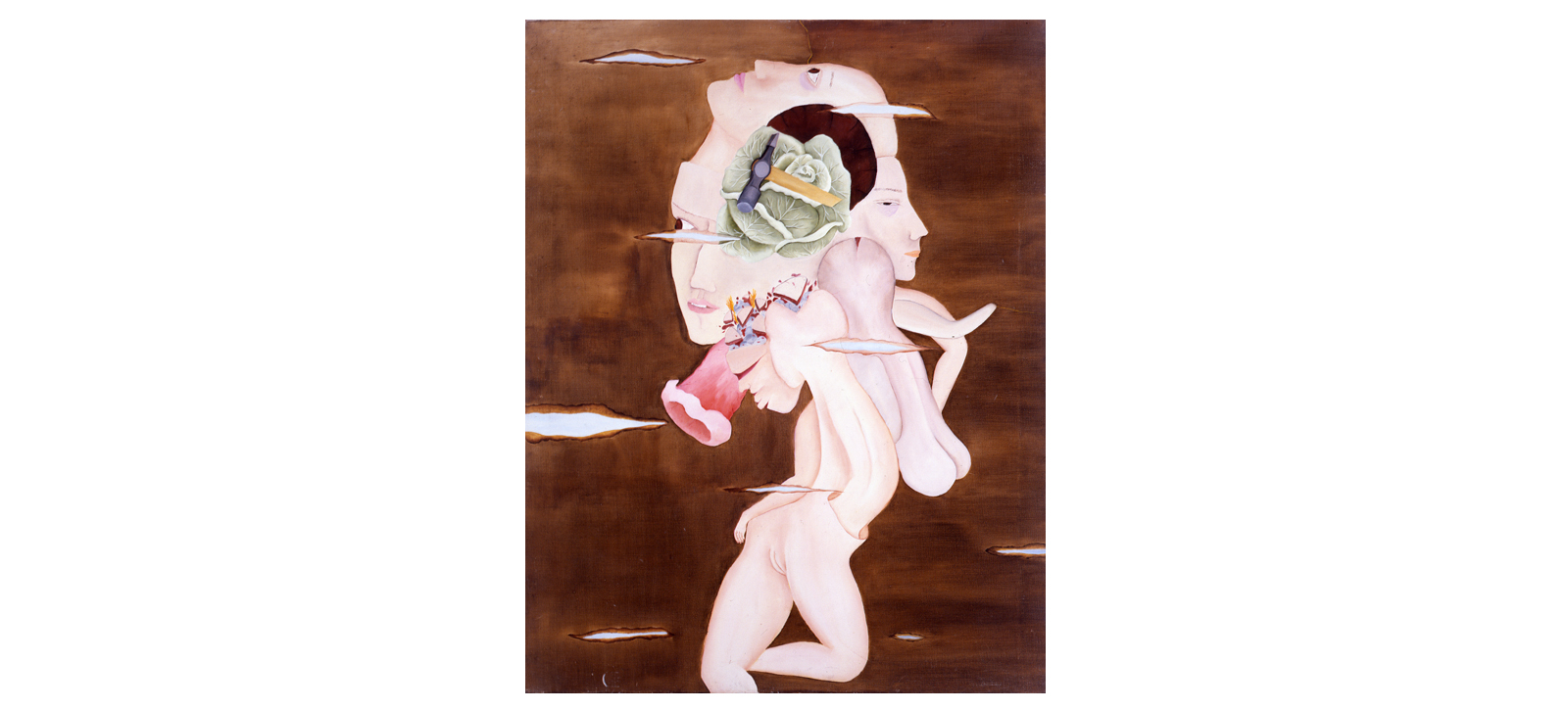

Angel de la Menstruación (1973)

Oil on canvas

48.2cm x57.1cm

Collection of the artist

"It was by chance that I discovered Cecilia Vicuña was not only a poet and an artist who made objects and installations but was also a painter. I knew that in her performances she wove together song and thread, drew on the long Andean tradition of the quipu and created the precarios, but it was during a visit to the New York studio she then shared with César Paternosto, at the time of their collaboration at the Drawing Centre, Dis solving, threads of water and light, in 2002, that one of her early paintings came to light. I can’t now remember how this happened, only that I was completely bowled over by the painting, which was like nothing else I knew, but somehow recognised immediately. It was an extraordinarily satisfying picture that created its own world, very clearly and simply.

From that moment it has been our dream to organise an exhibition of these paintings from the early 1970s which, as she told me in a letter of March 11, 2003, she had kept 'hidden,' or 'forgotten,' for so long. The first painting I saw was Angel de la menstruación, and the first attempts I made to write about it, from memory, responded to its very direct physical impact, the way that the figure fills and even exceeds the canvas. In memory I recalled this and the few other paintings I subsequently saw as much larger than they actually are. This was probably because there was a boldness to the image, a way in which it was, if not exactly poster-like, at least in some way public, a proclamation of being female. It seemed to be marking out new ground in a visual and poetic expression of the personal, the political and their interconnections, with a great deal of humour. The original title was Manraja or the Angel of Menstruation and it was painted in April 1973, in London. 'Manraja: a word derived from cunt and huge.' The painting celebrates the return of menstruation, a taboo subject, 'a portrait of the blood coming out of the vagina as beautiful clots.' She had painted clots of blood before but no-one realised what they were. The clots, she said, reminded her of de Kooning’s shapes and colours, 'although here they don’t look like this.' She (it is a self-portrait) is floating or flying 'on the air above the olive green killed by the titanium white,' 'with a snake of sand' that stretches like an extra limb across the canvas. She plays with a string that circles her body: 'I am part of a cosmic weaving, nothing is separate from everything else.' Springing up at either edge of the canvas are spiky branches, like an unwoven crown of thorns. Two tightly woven blood-red plaits frame her face and her eyes are red 'because I use my blood for looking.'

—Dawn Adès, from Cecilia Vicuña’s Calcomanías [full text]

Paintings